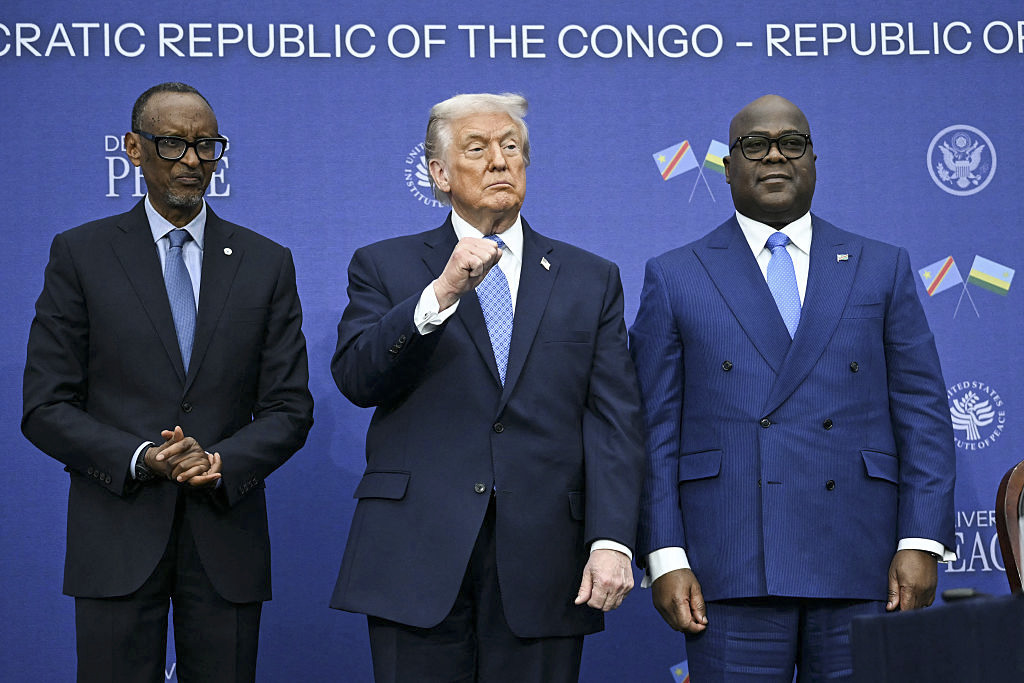

Trump to host two African leaders! That was a footnote to world news last week still dominated by efforts to stop the Ukraine war.

However, to those who follow African affairs, the triangular meeting at the White House looked like a miracle.

Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi and his Rwandan counterpart Paul Kagame seemed determined to end a decades-long war that, despite claiming at least as many victims as the current war in Ukraine or the recent war in Gaza, never hit global headlines.

The draft prepared by the White House was labeled "Peace and Economic Agreement" thus injecting the invisible hand of money into a conflict clothed in flimsy conceptual garments such as "national honor" and "sovereignty".

US President Donald Trump wasn't drafted and did none of the things that budding politically correct gurus counseled.

Instead, he tried to make money, not always successfully, but he learned to distinguish the tangible from the intangible. By instinct he learned that getting money by making deals, or if you look for pseudo-academic cliché, securing economic advantages, could also be used to stop wars.

Napoleon had quipped "cherchez la femme" (look for the woman) as the root cause of conflicts.

Trump re-wrote that as "cherchez l'argent". This is why in all his attempts at conflict resolution, from the Middle East to the Indian Subcontinent, Transcaucasia, the Korean Peninsula, and even "the Iran problem" that defies all logic, Trump has invited protagonists to come along and "let us get rich or richer together!"

The other night on French television, a former diplomat was mocking Trump for "ignoring rules and protocols of diplomacy" by even haggling with foreign leaders on live television at the White House. He also described as "unorthodox" the Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner tandem that has replaced traditional and career diplomats as negotiators of peace deals.

It was curious that in the Kremlin meeting between Russian President Vladimir Putin and the American duo there was no sign of US Secretary of State Marco Rubio or his Russian counterpart, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. Putin was flanked by his business advisers.

But what if the duo of Witkoff and Kushner can achieve what traditional career diplomats can't?

Critics of the Trump method resent the fact that in all his peace-making moves, he injects an element of American economic interest. What critics ignore is that getting the US involved economically could be a guarantee of durability for a peace deal. To them, making money from peace is worse than making it from war.

Some critics mock it as "fast diplomacy" with reference to the billions of fast-food hamburgers eaten each day across the globe with no one asking how many are digested.

The point is that they feed the hungry.

In almost all wars, the core of the conflict is access to resources that could provide the money needed to rule a country. Congo and Rwanda, for example, are fighting over the mineral resources of Goma and Bukavu, the once comical "kingdom" of Albert Kalonji. To get their shares, Congo and Rwanda have to spend part of the proceeds on military units and mercenaries to protect the Western companies that mine and market the coveted minerals.

The proposed Trump deal will eliminate the need for such forces; something like ending protection payments to the Mafia.

Right now, at least 10 more or less hot war situations pockmark the globe. In Sudan, two military factions are engaged in a massive fratricide with an adjunct tragedy in Darfur. In Libya, three factions are engaged in a similar power struggle. In both cases, money is the lubricant, and getting more of it is the ultimate aim of all factions.

What Trump offers is a method of persuading rival factions that they could make more money by sharing the resources rather than spending it on war, even if you need to give the US a cut as the go-between.

Elsewhere, for example in Gaza, money pumped in from outside enables groups like Hamas to devote all their resources to preparation for war and terrorism, while foreign donors cover the need for food, health, housing, education and even culture.

It might sound fanciful, but Trump's dream of turning Gaza into a well-located piece of real estate on which to build a new Singapore on the Mediterranean shouldn't be dismissed as an alternative to tunnel-digging for terror.

Russia, too, could make more money by ending the war in Ukraine than by pursuing an ever-receding goal of planting its flag in Kyiv. Right now, Putin is offering up to $80,000 to Russian or foreign mercenaries for a six-month stint at the war front to replace the 1,200 dead or wounded that, according to best estimates, Russian forces sustain each week.

In western Yemen, a good part of the cost of government and 60% of food needed are donated by "benefactors" thus enabling Houthis to act as a war machine while agriculture is devoted to growing qat to chew rather than food to eat.

In Jafar Panahi's new film "A Simple Incident," the character Iqbal, a former Iranian "defender of the harem" in Syria, confesses that he volunteered to kill Syrians in exchange for money that enabled him to own a house and look after his family.

And how many Lebanese might have joined Hezbollah without "certain advantages" that, according to Heshmat-Allah Falahat-Pisheh, a former member of Islamic Majlis in Tehran, offered a living standard higher than in Iran?

When Trump was a budding businessman, the Beatles sang "Money can't buy me love!" while he chanted "Money, money, money!"

His tune is: Money can buy you peace! Well, maybe.

Amir Taheri was the executive editor-in-chief of the daily Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. He has worked at or written for innumerable publications, published eleven books, and has been a columnist for Asharq Al-Awsat since 1987.

Gatestone Institute would like to thank the author for his kind permission to reprint this article in slightly different form from Asharq Al-Awsat. He graciously serves as Chairman of Gatestone Europe.