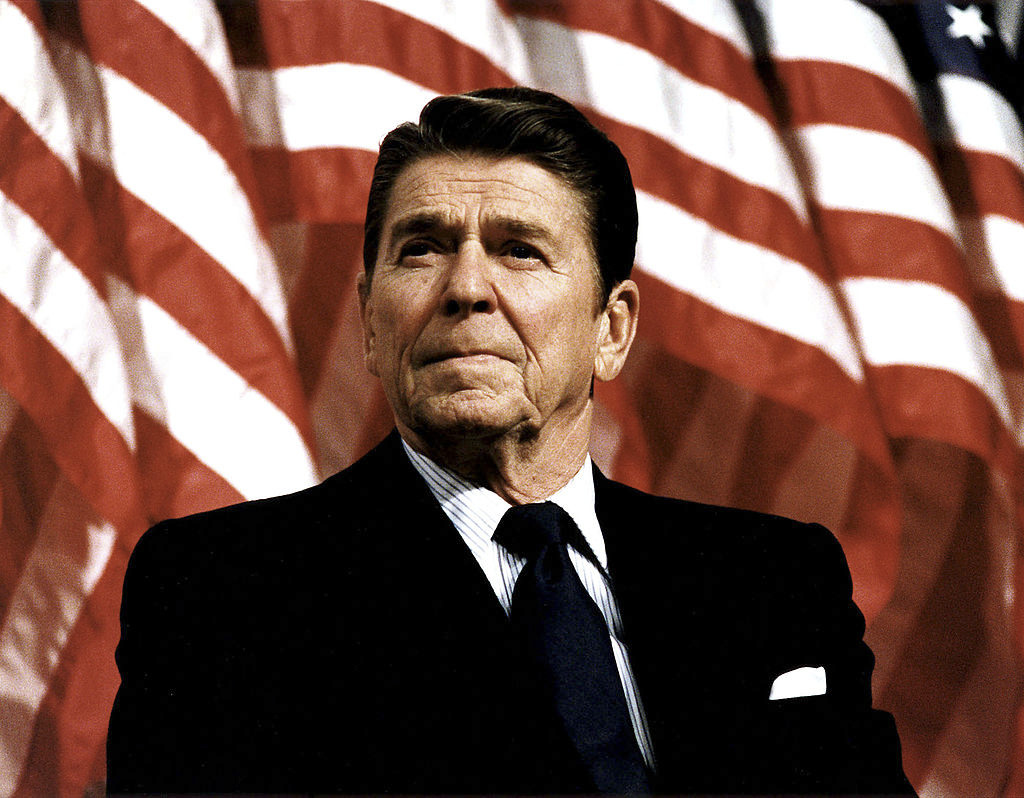

When US President Ronald Reagan revived the phrase "shining city on a hill," he did so not as a marketing flourish but as a governing ethic: the United States would deter evil by projecting confidence, prosperity and moral clarity.

His message blended optimism with hard power — lower taxes and deregulation to spur growth, rebuilding the military to restore deterrence, and an unapologetic defense of Western civilization. The mix resonated because it tied virtue to results: fewer hostages, a stronger dollar, and an adversary in Moscow forced onto its back foot. This fusion of ideals and outcomes gave the GOP a compass that pointed true north.

Reagan called it "peace through strength." The logic was simple: credible power restrains predators, and free economies outrun "planned" ones. That worldview, articulated in the 1980s and vindicated by the collapse of the Soviet bloc, set a high bar for a new statecraft. This new statecraft, begun by Reagan, was neither isolationist nor utopian. It was positive and pragmatic, based on whatever might work, rather than confined by ideological strictures. Its successes—such as revitalized growth, a revived military and renewed national morale — have given the US a strategic steadiness.

After the Cold War, however, the glue that had held these policies together began to loosen. Without an existential foe, Washington elites seemed to drift toward a missionary impulse: the United States would not only deter threats but also refashion distant societies in terms of national security – both theirs and ours in the West.

In Iraq, the amazing, quick war devolved into an incompetently executed, grinding occupation that cost lives, treasure, and strategic trust. The outcome was not American moral authority but a credibility gap that emboldened adversaries and internationally damaged faith in America's judgment.

Libya offered a bipartisan variation on the same error: intervention but without a realistic plan, especially in the event of unexpected consequences. The result was -- and sadly remains -- a failed state whose instability has radiated across North Africa and into Europe.

As the foreign policy establishment chased missions abroad, it neglected duties at home. Factories closed, addiction surged, and border chaos mounted. Large segments of Middle America concluded that the government, while pursuing possibly noble ideals, might be ignoring tangible harms. Both political parties, once fluent in kitchen‑table economics and national pride, often sounded like seminars rather than positive results, for instance, a functional education for its citizens or "affordable healthcare" that was actually affordable.

Into this vacuum came a businessman, speaking a language voters understood: borders, jobs, sovereignty and global respect. He did not reject American leadership; he redefined it as the capacity to secure the interests of American citizens. Tariffs – which some other countries had been imposing on the US – were not "taxes" or theology; they were instruments of geopolitical persuasion other than war. Alliances were tools to strengthen America's military breadth. Diplomacy was to be measured by outcomes—defeated terrorists, deterred adversaries, reshored industries — not by applause at international conferences.

On China, the government's new hard look at reality ended decades of wishful thinking that economic engagement alone would liberalize a Communist party‑state. By imposing tariffs and spotlighting technology theft, supply chain vulnerabilities, and the national security stakes of having handed over American jobs to its adversaries, he forced a reconsideration of how much malign behavior it is advisable to tolerate.

Communist China, in 1990, had already declared a "Peoples War" – meaning all-out war – on the US. Today, even critics of the government's policies concede that fending off this aggressor, which has openly stated that it plans to displace the US as the world's leading superpower, began with his break from the old orthodoxy of "competition" eventually leading China to evolving into an open, democratic society.

On the Middle East, the government rediscovered deterrence: making it clear -- credibly -- to enemies that the cost to them of aggression would be catastrophically high. The ISIS caliphate was crushed; the air strike that killed the Iranian terrorist Qasem Soleimani reestablished red lines against all terrorists, and the Abraham Accords demonstrated that Arab‑Israeli normalization could advance without yielding to demands from rejectionist groups. This combination—force where necessary, diplomacy only where useful—restored a sense that American power could achieve concrete, stabilizing gains.

Critics called this "transactional" – perhaps another word for accountable. Looking at "what works" demands that leaders match means to ends and judge policies by what they deliver. Under this lens, moral posturing is not a virtue; it is vanity. A nation that promises to save the world while failing to protect its own communities is not moral—it is at best negligent, at worst catastrophically destructive, as can be seen in much of Europe.

Former US administrations sought appeasement to avoid "escalation" (here, here, here, here and here). While members of the current government can be blunt -- even abrasive -- they have nevertheless re‑centered the only important question: does a policy actually help Americans, Europeans, or whomever is possibly being bamboozled?

What looks like "moral righteousness" often compounds the problem: it depends on who thinks what is "moral." Many seem to have recast foreign policy as "virtue signaling": proclamations (here, here and here), hashtags, and ambitious frameworks that unravel upon contact with reality. Multilateral consensus, as over "climate change," is confused with legitimacy, and national borders are treated as embarrassments rather than as obligations to protect one's citizens for national security. This is not compassion; again, it is vanity -- abdication cloaked as empathy.

Pragmatic, unsentimental realism is not cynical: it assumes that safeguarding a nation requires enforceable borders, credible deterrence and growing paychecks. The surest way to defend a nation is to maintain one strong enough to deter predators and prosperous enough to inspire emulation. Reagan understood this; the current government revived the same policy in an even harsher international climate. Both rejected the illusion that words alone can police the world.

Economically, strength means reconnecting trade policy to national self-reliance. The pandemic exposed the folly of having offshored critical industries, from medicine to semiconductors. An on-the-ground realism measures trade by the ability of people to buy goods -- especially working-class and middle‑class prosperity -- not by aggregate charts that disguise regional collapse. When a policy hollows out cities, it hollows out the ability of people to live there in safety and in comfort.

On immigration, a healthy sovereign nation distinguishes between lawful, welcome entry, and unlawful, entry -- sometimes by people who do not share the values of the host country, or who may be criminals, or who are determined to take it down. A healthy sovereign nation honors citizens who follow the laws, enabling people to live safely together, and that protects the vulnerable from predators. While an unsecured border may sound humane; it is often seen as an invitation for abuse. America's current call for enforcement — walls, technology, remain‑in‑Mexico, interior checks — should be judged by results: fewer deaths, less fentanyl and safer streets.

In much of the non-progressive world -- often referred to as "far right," although everyone probably thinks he is "center" -- parents have demanded authority over schools; communities have demanded order over mayhem. These are not "culture war" distractions; they are the preconditions for self‑government. A nation that cannot safeguard historical truth in classrooms -- such as if there "really" was a Holocaust or an October 7, 2023 -- will, one hopes, have a hard time projecting any kind of worldwide leadership.

Internationally, if you are no-nonsense, you choose your priorities. The United States faces simultaneous challenges from China's aggression, Russia's expansion, and Iran's terror networks. The United States cannot meet them with "slogans." It needs steady, vast defense spending; energy dominance – most urgently from developing nuclear fusion energy with which China is racing ahead, rather than US addiction to low-hanging nuclear fission energy. The US also needs secure supply chains, and a diplomatic posture that rewards friends and deters foes. That is not isolationism; it is national security.

The political throughline is therefore to align means with ends, rhetoric with reality, and "morality" with beneficial, measurable results. Reagan ended stagflation and the Cold War; President Donald J. Trump ended ISIS's caliphate and upended a failing, complacent consensus on both China and "open borders." Both presidents faced critics who mistook their policies for cruelty. Both proved that purpose without power is fantasy—and power without purpose is waste.

There are risks, of course. Populism can drift into grievance. Some politicians, perversely, seem to obstruct their constituents from flourishing – perhaps to keep them dependent on promises always just a nose in front of them; perhaps to thwart accomplishments by another political party to prevent one's own deficiencies from being exposed. The antidote is the Constitution — checks and balances, federalism that gives power to the states, and public debate that keeps leaders tethered to positive results. All parties not solely interested in becoming a tyranny -- acquiring power for its own sake -- would do well to channel popular energy toward several outcomes: fair elections that would not need contesting; empowering parents; providing lawful streets, and backing an economy that, while ensuring a safety net for those who cannot work, nevertheless rewards work and keeping families together.

Demands in NATO to share the economic burden have resulted in higher European defense spending. The move of the U.S. Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem broke a diplomatic taboo and anticipated the Abraham Accords. Energy policy that favored U.S. production lowered prices and limited the leverage of Russia and other petro‑tyrants. These are not applause lines; they are concrete metrics.

The mandate for all political parties in the US is sober: keep the peace by reminding enemies, credibly, that the cost of aggression would be far too high; revive industry and the economy by rewarding production and allowing people to keep more of what they earn; secure the border either by enforcing immigration laws or demanding that Congress change them, and project confidence without sounding overbearing. That is how a republic is preserved.

Patriotism is a responsibility to one's fellow citizens. Compassion is not open borders; it is a lawful system that protects the weak from cartels and terrorists. International leadership is a quiet credibility earned when adversaries hesitate and partners invest. These are hardheaded virtues that some former administrations have celebrated and that the current one — despite rough edges — has resurrected.

In the end, America's moral compass does not swing with fashions. It is anchored to the permanent values: the inviolability of the individual, the rule of law, freedom of speech and protecting its citizens from abuse -- including from the government. The challenge for America's political parties is to turn these principles into ways of life that families can enjoy and that adversaries respect.

Power, wisely used, becomes peace.

Pierre Rehov, who holds a law degree from Paris-Assas, is a French reporter, novelist and documentary filmmaker. He is the author of six novels, including "Beyond Red Lines", " The Third Testament" and "Red Eden", translated from French. His latest essay on the aftermath of the October 7 massacre " 7 octobre - La riposte " became a bestseller in France.As a filmmaker, he has produced and directed 17 documentaries, many photographed at high risk in Middle Eastern war zones, and focusing on terrorism, media bias, and the persecution of Christians. His latest documentary, "Pogrom(s)" highlights the context of ancient Jew hatred within Muslim civilization as the main force behind the October 7 massacre.