Russia is providing equipment, technology, and training to China for an airborne invasion, the Washington Post reported on September 26. The report, based on a study issued by the U.K.-based Royal United Services Institute, notes that China is planning an airborne assault on Taiwan.

The day before the Washington Post article, Reuters revealed that Chinese experts had traveled to Russia to help that country develop drones. According to the wire service, Sichuan AEE, a Chinese company, sold attack and surveillance drones to Russian company IEMZ Kupol through an intermediary sanctioned by the U.S. and the EU.

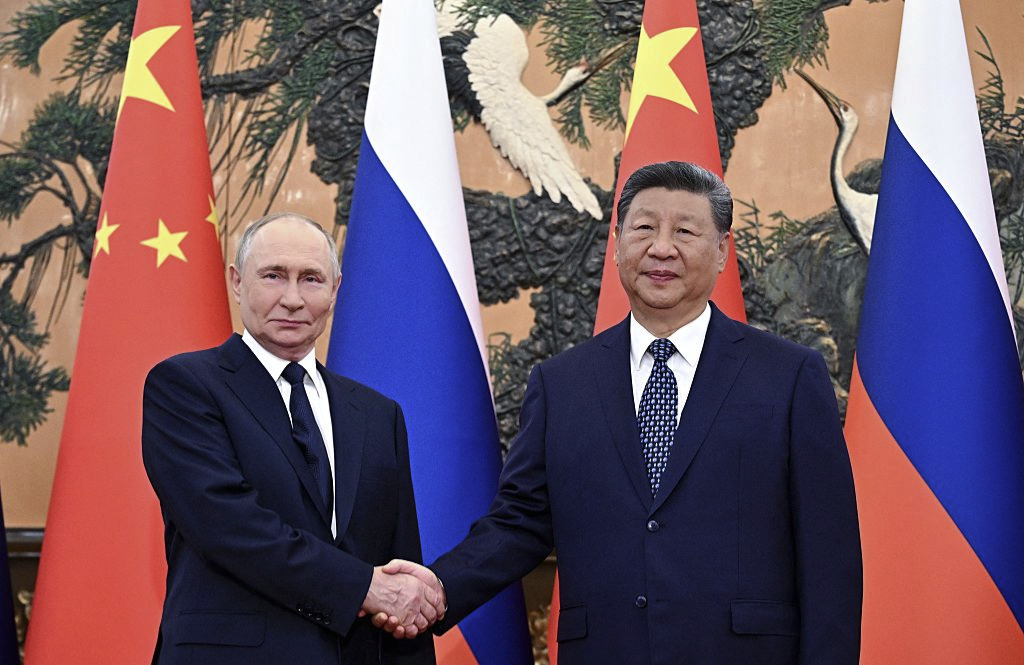

The two reports highlight the close cooperation between Russia and China in military theaters around the world. These two aggressive states, from all appearances, have effectively formed a military alliance.

Many in the American policy community, clinging to a post-Cold War world that no longer exists, had been confident that Beijing and Moscow could be managed and perhaps separated. Now, it is clear those expectations were unrealistic, and it is time to recognize that the free world faces implacable enemies who have formed an enduring bond.

Beijing and Moscow, after the Cold War, wasted little time in taking down the international system. The Chinese and Russian militaries conducted their first large-scale joint military exercise in 2005 and since then have participated in regular exercises across the Eurasian landmass and in nearby waters.

Yet they are doing more than just preparing for conflict. In North Africa, both have been fueling insurgencies and have almost certainly been coordinating efforts. China has been providing all-in support, including sending soldiers, for Russia's war against Ukraine. Both Beijing and Moscow have aided Iran's rearmament and assault on Israel. In the Western Hemisphere, the Chinese and Russians together back the Cuban and Venezuelan regimes.

How did China and Russia, so weak after the Cold War, become such threats? America tried to integrate both into the international system with trade and investment and paved their way into the institutions of the rules-based order. Beijing and Moscow, however, rejected that order and are using newfound strength to challenge it.

Worse, after the Cold War, American presidents were more worried about the stability of the Chinese and Russian ruling groups than the fundamental challenges they posed. As a result, Washington imposed few costs on their disruptive conduct.

American efforts went too far, especially with regard to China. For instance, President George H.W. Bush surreptitiously worked to bolster the Chinese Communist Party in the immediate wake of the horrific slaughter in Beijing in June 1989. He even sent National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft on a secret mission just a month after the massacre to assure Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping that the U.S. supported his murderous regime.

Moreover, U.S. presidents tried to keep Russian autocrats in power. This is from Ambassador Douglas Lute, then America's permanent representative to NATO, at the Aspen Security Forum Global in London on April 22, 2016:

"So essentially there's a sense that, yes, there's a new more assertive, maybe even more aggressive Russia, but fundamentally Russia is a state in decline. And we have conversations in NATO headquarters about states in decline and arrive at two fundamental models: States in rapid decline, which typically lead to chaos and break-down, and states in gradual decline. And we ask ourselves which of these two models would we have our nearest, most militarily capable neighbor with thousands of nuclear weapons move along. Obviously trying to manage Russia's decline seems more attractive than a failed state of that size and magnitude on NATO's border...

"And if you accept the premises that we've heard here about Russia's internal weakness and perhaps steady decline and so forth, it may not make sense to push further now, and maybe even — and maybe accelerate or destabilize that decline."

This approach, questionable even then, still guides American policy. "When it comes to Russia, the Trump administration, like most European governments, has two mutually incompatible goals," Air Force General Blaine Holt, who served as America's deputy military representative to NATO, told Gatestone.

"American policymakers want to make sure that Ukraine does not lose and at the same time that the government of Vladimir Putin remains intact and stable. It is unlikely Washington can have both. Soon, it will have to choose one or the other."

Holt, now retired, is correct. Trump's plan is not working. Russia's forces are making progress in Ukraine, and, viewing the response of the great democracies to his invasion as feeble, Putin is already taking on other neighbors. September, for instance, has been a big month for incursions in the skies above NATO members. On the 9th, at least 19 Russian drones intruded into Polish airspace. On the 19th, three Mig-31s flew over Estonia for 12 minutes. Both Romania and Latvia charge that Russian drones entered their airspace in recent weeks.

In response to Russia's provocations, Defense Minister Pal Jonson of NATO's newest member, Sweden, told the newspaper Aftonbladet that his country would shoot down intruding aircraft "with or without warning."

The Chinese are in war mode too. On July 2, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi told Kaja Kallas, the EU foreign policy chief, that Beijing does not want to see Russia lose in Ukraine because then the U.S. would focus on China in East Asia. China, by implication, also wants to see the war drag on to tie down the United States.

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte in December said that the organization's members needed to "shift to a wartime mindset." With China and Russia in fact waging war, Trump has already started the process by renaming the Pentagon the "Department of War." The West and friends are finally realizing how close they are to catastrophe.

Gordon G. Chang is the author of Plan Red: China's Project to Destroy America, a Gatestone Institute distinguished senior fellow, and a member of its Advisory Board.